In a 2016 published survey, of the 14 most significant problems faced by Nigerians, corruption was ranked in third place, while healthcare was in fifth position. In the second version of the survey published in 2019, healthcare and corruption switched positions. And in 2023, corruption ranked in fourth position, and healthcare fifth.

Both corruption and healthcare have consistently remained problematic to Nigerians for decades. And one can only imagine what happens when the two problems intersect. Health corruption has been studied by the Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria (HPRG) and the Bayero University, Kano (BUK) for about seven years, leading to the establishment of the Health Anticorruption Project Advisory Committee (HAPAC), which is in partnership with the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR).

July 2024, health sector actors in Nigeria were, again, implicated in the third edition of the National Corruption Survey (NCS) published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) with support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. Key findings from the report suggest that the health sector ranks among the top-4 homes for bribery in Nigeria, manifesting in private health providers collecting bribes, and bribes paid for free services, to speed up procedures, or as an appreciation for care. Despite significant accounts of bribery within the health sector, reports or whistleblowing by service users who have been asked or forced to pay bribes were scarce.

Commendations to the UNODC and co-publishers

First, as stakeholders, we commend the efforts of the UNODC, NBS, and the supporting organisations for consistency in the conduct of the NCS, robustness of the sample, and data analytical rigour. We recognise that the organisations have been genuinely intentional about the issue, eliciting compelling and comparable data over the years, while open to improvements. The robustness of the sample manages errors and secures a good representation of Nigeria’s large population. Thus, we encourage continuity and sustainability of the survey as a means of tracking the progression or retrogression of sector-by-sector anticorruption efforts in Nigeria.

Special focus on the health sector

The NCS covers key sectors in Nigeria like security, education, judiciary, health, and public service. Over the years, it has significantly focused on bribes, the diverse forms they take, and the actors involved. In corroboration, academic and journalistic investigations affirm the prevalence of bribes in the health sector, also documented in some pieces of work as “informal payments”. Beyond bribes, scientific investigations have equally documented much more damaging corruption in the health sector like absenteeism of health workers, procurement fraud, health financing malfeasance, and employment irregularities.

Explaining the focus on bribes by the NCS, a representative of the UNODC reflected on Goal 16 of the sustainable development goals (SDGs), which targets substantial reduction of the prevalence of bribery if strong institutions must be built. The significance of achieving this target for the health sector cannot be overstated due to the sector accounting for the highest patronage (30 percent) by Nigerian citizens, even when compared to the Police – according to the survey.

For most health corruption enquiries, the private sector has been silent. So, the NCS has unlocked an area for future enquiries and anticorruption intervention by reporting the collection of bribes among medical doctors in private practice. Reacting to this, a representative of Nigerian private practitioners alluded to some corrupt practices happening within the system but had reservations about the significant indictment of medical doctors despite other health and non-health personnel delivering health services in the private sector.

On the way out of health corruption in Nigeria, available, efficient, and responsive reporting mechanisms must be present. Unfortunately, the NCS recorded no reports of bribery in the health sector. Comments from a participant who is familiar with the Medical & Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN) affirmed poor reporting of corrupt practices to authorities, suggesting an urgent need to build an efficient reporting mechanism for the health sector.

The representative also mentioned that some practitioners may be unaware of the content of the MDCN code abhorring some of such normalised practices like demanding informal payments and receiving gifts from service users. As stakeholders, we hope that the MDCN will scale up awareness of the contents of its code among practitioners using effective sensitization measures, including curriculum approaches.

Important takeaways to strengthen future National Corruption Survey as per the health sector and to improve anticorruption

While we commend the thoughts and efforts that have consistently gone into the production of the NCS, concerning the health sector, we recommend the following for consideration:

- The inclusion of more health sector corruption concerns like absenteeism, procurement irregularities, etc., based on available ranking in published academic outputs.

- The organisations should build partnerships with more stakeholders in corruption research.

- A good description of ‘other health workers’ (non-medical doctors) or apply the use of “health workers” as a common name for all health practitioners in the health system.

Overall, an important takeaway from the NCS for the health sector is that anticorruption agencies must now intensify their work with the health sector and grassroots leadership to mainstream efficient, user-friendly, and responsive reporting mechanisms at the points of health service provision. This can be co-produced with academics and investigative journalists who have historically worked on health corruption in Nigeria, as well as health workers, policymakers, and community representatives.

In all, HAPAC looks forward to the next national corruption survey, with the hope that lessons from the 2023 version will be used to improve the anticorruption prospects of the health sector. It also expects that data gathering and analysis for the health sector will benefit from engagements with health anticorruption scholars in Nigeria. HAPAC commends the NCS for finding its place within Goal 16 of the SDGs – Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions, which has strong implications for Goal 3 – Good health and wellbeing.

Click to download PDF version of the communique

Acknowledgement

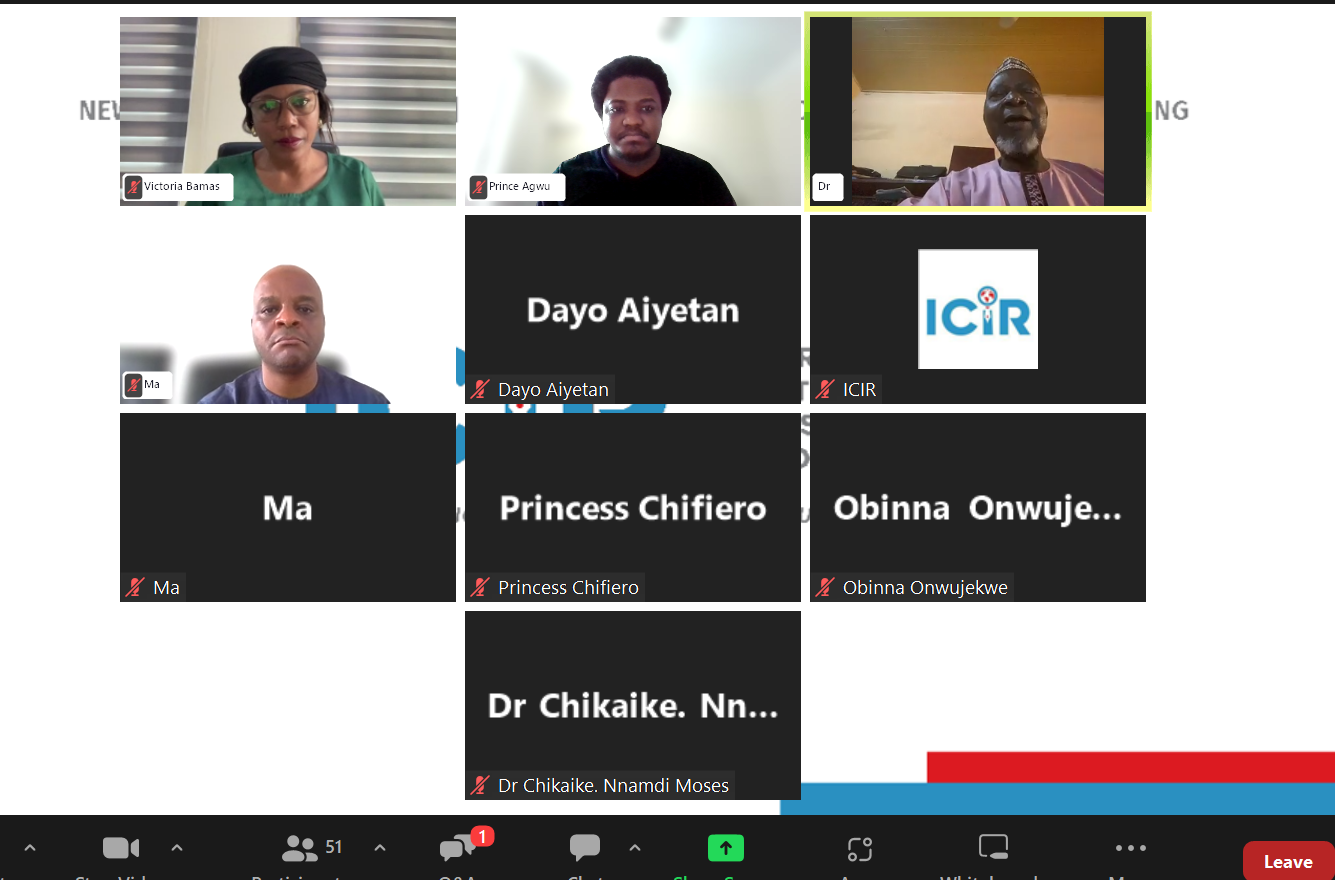

- Dr Idris Muhammad – Chairperson, HAPAC

- Dr Tarry Asoka – Deputy Chairperson, HAPAC

- Victoria Bamas – Secretary, HAPAC

- Professor Obinna Onwujekwe – Convener, HAPAC

- Dayo Aiyetan – ICIR

- Prof Muktar Gadanya – Bayero University, Kano

- Dr Moses, C – Association of Nigerian Private Medical Practitioners

- Princess Chifiero – United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)

- Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria (HPRG)

- Accountability in Action Research (AiA)

- SOAS-Anticorruption Evidence Consortium (SOAS-ACE)

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)

We thank Dr Prince Agwu for the review of the communique.

For correspondence, send an email to vbamas@icirnigeria.org, Cc prince.agwu@unn.edu.ng