Children from 12 to 23 months old who have not received any vaccinations are referred to as ‘zero-dose’, with approximately 2.1 million such children residing in Nigeria, representing the highest figure globally. It’s crucial to administer essential vaccines, such as the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis-containing vaccine (DPT1), before a child’s first birthday. These vaccines primarily protect Nigerian children from diseases that vaccines can effectively prevent, including diphtheria, polio, measles, pertussis, and rotavirus. Alarmingly, around 40% of child deaths in Nigeria before the age of five are attributed to vaccine-preventable illnesses. This high figure raises questions about the actions that must be taken from now on.

At the invitation of the Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria (HPRG), stakeholders involved in immunisation at the federal and state levels, including representatives from the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology, the Association of Local Governments of Nigeria (ALGON), the Nigerian Governors’ Forum (NGF), and Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), convened at the Sandralia Hotel in Abuja on 7th and 8th May to devise a way forward for addressing zero-dose.

The invited stakeholders raised concerns regarding the investment in vaccine procurement and distribution, which exceeds US$ 100 million annually (counterpart funding), failing to achieve full vaccination coverage. Currently, less than 40% of children in Nigeria around the age of two are completely vaccinated. Notably, there was a shared agreement among stakeholders that the issue of zero-dose should not be the sole responsibility of the health sector. With this in mind, the stakeholders moved forward to collaboratively identify the problems, determine who should participate in addressing them, and identify effective solutions.

Stakeholders agree on what the problems are – The What

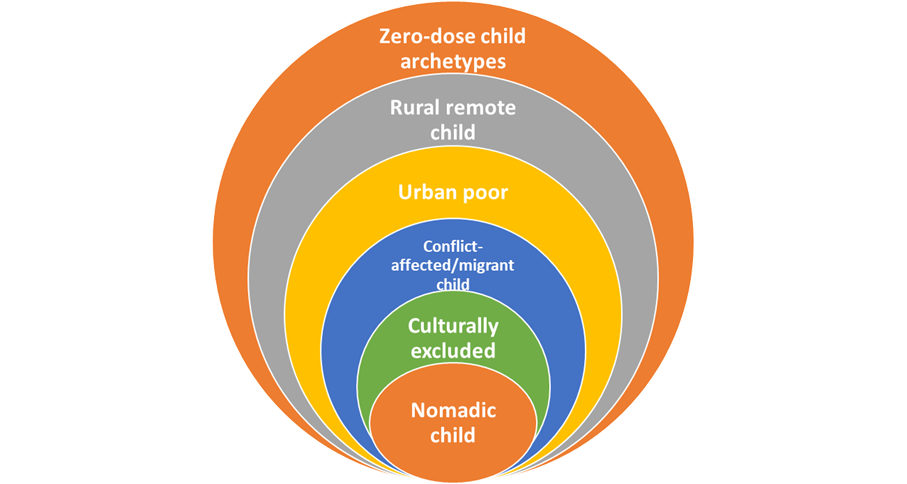

Following an initial review of documents conducted by the HPRG, the stakeholders needed to validate the findings. This began with the collective identification of the common characteristics or archetypes of a typical zero-dose child. It was agreed that zero-dose children typically reside in rural-remote areas, urban slums, or conflict-affected regions; also, they are born to nomadic parents or affected by forced migration; they equally include children born into households that can be classified as urban poor and those that adhere to superstitions and cultural beliefs opposing vaccines.

We identified various reasons for the zero-dose situations in the various archetypes. Some factors are cross-cutting across the archetypes, while some are peculiar. Factors such as education level, poverty, vaccine hesitancy, distrust, misinformation, gender issues related to maternal disempowerment, conflicts and displacement, and religious and cultural restrictions were identified to play a role in fueling the zero-dose problem. Several peculiar as well as cross-cutting immunization system issues were also identified. These include corruption and inefficiencies in the system, which manifest as vaccinators being unavailable at their duty posts, inflating the numbers of children vaccinated and marking fingers of non-immunised children during immunisation campaigns.

Figure 1: The archetypes of a typical zero-dose child

Other identified challenges include an over-reliance on external funding, duplication and multiplication of roles and activities in the immunisation space, weak coordination among partners and stakeholders in the immunisation system, data quality issues, unavailability of recent and accurate data for planning immunisation campaigns, inadequate policies for enforcing immunisation, and systemic exclusion of hard-to-reach children due to limited availability of mobile clinics and security for vaccinators. A consensus emerged that the issue of zero-dose children is not merely a matter of missed vaccinations but a systemic problem.

Stakeholders identify who should be involved in tackling zero-dose – The Who

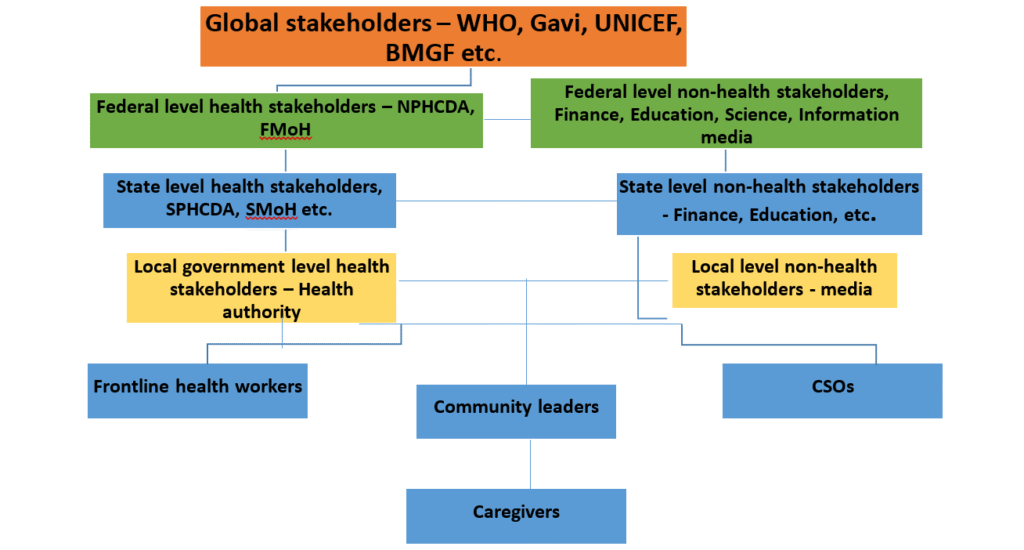

The causes of zero-dose are diverse, as emphasised by the stakeholders, which implies that various sectors must unite to address them. Along with the researchers from HPRG, sectors such as education, finance, media, security, civil society, and community leaders, among others, were identified as key players in tackling zero-dose. Below is a diagram illustrating the suggested actors that must be involved. Overall, emphasis was placed on decentralising cross-sectoral collaborations to the level of local governments. However, evidence-based operational plans for multisectoral collaborations in addressing zero-dose are lacking. For this reason, this study has been initiated under the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research.

Figure 2: Graphic representation of immunisation stakeholders

Stakeholders contributed early thoughts to what can work – The How

Although it is still early days, some stakeholders have leveraged their lived experiences within the vaccination system to highlight essential considerations regarding what might work in addressing zero-dose issues. Firstly, it was noted that cultural, religious, and political variations between northern and southern Nigeria would influence potential solutions. Consequently, there were suggestions for bespoke and context-specific approaches. Secondly, the buy-in from locals is essential. This means that any co-production activities aimed at developing solutions that exclude locals are likely to fail. The health sector should ensure proper coordination of immunisation efforts, collaborate with other sectors, and enhance local ownership of immunisation activities.

Going forward

The workshop clearly outlined the concept of the zero-dose child, the challenges posed by zero-dose children, the immunisation system, and the various stakeholders involved. Therefore, the question is no longer whether we understand the issue or can identify the zero-dose child. Instead, the focus shifts to how we, as stakeholders, can collectively address this challenge. Our project is advancing to the next phase, which involves field studies across the six geopolitical zones (Abia, Bauchi, Cross River, Kano, Nassarawa, and Oyo) to identify local and contextual factors contributing to the issue of zero-dose children. We will keep you updated here as we progress, and we are confident that the findings from our study will help Nigeria achieve its goal of reducing the number of zero-dose children by 80% by the end of 2028.

Authors

Prof. Chinyere Mbachu, Dr. Chinazom Ekwueme, Dr. Prince Agwu, and Prof. Obinna Onwujekwe

Acknowledgement

We warmly thank HPRG researchers and participants who were actively involved in the workshop.

Photos