In urban slums across Nigeria, formal healthcare providers like the primary health facilities are characterised by poor patronage, often due to factors of high cost and inefficient service delivery. This has led to high patronage of patent medicine vendors (PMVs) or chemists, who are trusted by communities, accessible, and cost-friendly, yet often operating outside defined regulations of the formal health system. While PMVs fulfil an important role, their practice of selling antimicrobials, often called antibiotics, without a prescription raises serious concerns about antimicrobial resistance (AMR). AMR occurs when germs mutate and become resistant to medicines that would normally eliminate them, leading to treatment difficulties, increased spread of diseases, and a higher risk of death.

As PMVs are now deeply integrated into these urban slums, primarily due to the shortcomings of formal health services, their role in combating AMR has become crucial and indispensable. Could PMVs, therefore, become key partners in combating this global health threat of AMR, especially in urban slums where issues such as poverty, social exclusion, overcrowding, and limited access to essential services like healthcare are prevalent?

AMR is a silent, growing public health threat

The misuse of antibiotics or antimicrobials such as ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, amoxicillin, and others, which are marketed under brand names like Flagyl, Augmentin, Amoxil, Ampiclox, and Ampicillin, has become widespread in Nigeria. According to data, 42% of adults misuse antimicrobials, and only 68% follow proper prescription guidance. This has resulted in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) becoming widespread, threatening Nigeria’s health security and placing a burden on global public health. A key underlying factor is that the sale of medicines in Nigeria remains largely unregulated, due to the dominance of PMVs who have built community trust and an organisational structure capable of challenging formal health authorities.

According to the Pharmacy Council of Nigeria, there are only about 19,000 licensed pharmacists nationwide, catering to a population of over 220 million people. Of those licensed pharmacists, over 2,800 left Nigeria for better opportunities between 2018 and 2023. Moreover, approximately 200,000 PMVs operate nationwide. Thus, in many underserved areas such as urban slums, PMVs dominate the medicines market, as licensed pharmacists usually focus on wealthier neighbourhoods. Unfortunately, the highly inefficient primary health facilities in urban slums have worsened the situation, leaving urban residents with PMVs as their most accessible option for medicines.

The unregulated sale of antibiotics, frequently without prescriptions, is speeding up the spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This results in longer hospital stays, treatment failures, and higher death rates. These issues also impact government healthcare costs and reduce overall population productivity.

The concerns mentioned earlier have motivated the Health Policy Research Group (HPRG) at the University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus, with support from the CHORUS Urban Health Consortium, to conduct a study in Ebonyi State, southeastern Nigeria. This research focuses on the quality and dispensing patterns of over-the-counter antimicrobials, as well as how urban slum residents utilise these medications.

With the rise in AMR, are PMVs trusted community health providers or hidden threats?

PMVs are far more than just drug vendors; many residents refer to them as actual “doctors” and trust them as their primary healthcare providers when illness occurs. They are familiar, accessible, and offer affordable ways to buy medicines, which makes them popular among urban slum residents. Additionally, as urban slum residents find it difficult to access formal healthcare providers like medical doctors, PMVs have become even more like health messiahs in the communities they serve.

“…they [urban slum dwellers] have no way to easily contact a medical doctor; they regard us as their doctor” – Male PMV, 45

Why do PMVs sell antibiotics without prescription?

In our study, we found that PMVs sell antibiotics without prescriptions, often for incorrect conditions, which poses a risk for antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This dispensing behaviour results from a complex interplay of economic factors, social expectations, and cultural norms influencing both providers and consumers in urban slums. We identified four primary drivers:

Client Pressure: Customers expect instant access to medications. If one PMV refuses, another may agree, so vendors feel compelled to meet expectations to keep their business.

“…If you tell them to go and meet a doctor… they will meet the same class of people like us in another shop… so in such a case, you sell the medicine to him [without prescription].” – Male PMV, 41

Economic Survival: PMVs depend on daily medicine sales to survive. Turning away a customer results in lost income, which can make it difficult to maintain ethical practices.

Influence of subcultural norms in society: Cultural norms and health misconceptions further complicate the situation. Many community members and some PMVs believe antimicrobials can cure nearly all illnesses. For example, it is common to sell antibiotics alongside antimalarials for treating malaria. It is also usual to combine multiple drugs without guidance, and many depend on advice from family or past experiences. These beliefs promote irrational use and diminish the effectiveness of life-saving medicines.

Weak Regulatory Oversight: Stakeholder interviews consistently highlight weak regulation as a key factor enabling the improper sale of antimicrobials. Despite laws banning the sale of prescription drugs like antibiotics by PMVs, these sales often happen with minimal supervision. Enforcement is hindered by inadequate staffing, limited funding, and weak accountability mechanisms, allowing PMVs to operate with little oversight. Consequently, they tend to focus more on keeping their businesses running than on safeguarding public health.

“When you have a system where there is low regulatory supervision, of course everybody will go gaga and want to do anything that he thinks will bring him money…” – Male, Policymaker, 54

This combination of lax oversight, client pressure, and economic need has led to the normalisation of inappropriate antimicrobial dispensing among PMVs.

Who’s most affected by poor prescription of antimicrobials?

The residents of Abakaliki’s slum areas, including Nkaliki, Kpirikpiri, and Hausa Quarters, are mainly low-income earners and informal workers. Like every other urban slums, these households typically experience overcrowding, poor housing conditions, limited clean water access, and inadequate sanitation. In Hausa Quarters, longstanding settlers from northern Nigeria live alongside indigenous locals, often in crowded settings. Women, the poor, and individuals with little or no formal education face the biggest obstacles to accessing formal healthcare. For these groups, PMVs and self-treatment are not just matters of convenience; they are often their only viable healthcare choices. As a community member states:

“Sometimes the need may be urgent, and the money I have may not be enough to go to the hospital, but if I go to the chemist, I can buy medicine from them, and by the grace of God, it will work.”– Female participant, Nkaliki.

These social inequalities perpetuate informal and unregulated treatment practices, hindering efforts to improve adherence to antimicrobial prescriptions and guidelines.

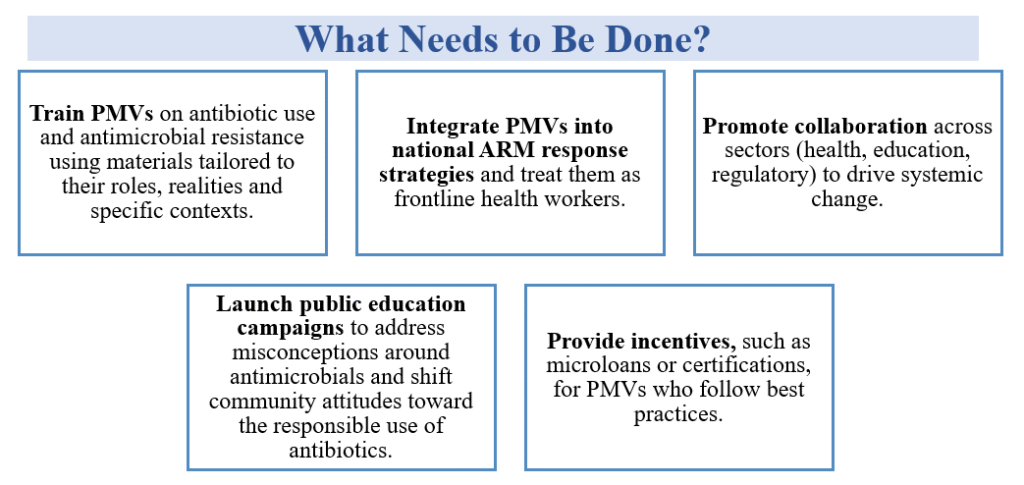

A pathway forward: engage PMVs as partners, less of punishment

Despite obstacles, PMVs can contribute to solutions. Many are willing to improve their practices if they receive proper training, recognition, and support. Instead of relying only on enforcement, a balanced strategy is essential—one that combines capacity-building, incentives, and clear, enforceable regulations. This approach not only encourages compliance but also fosters trust and accountability. Treating PMVs as partners, with appropriate oversight, provides a practical, people-centered way to promote responsible antimicrobial use and reduce the spread of AMR.

Conclusion

PMVs are already at the forefront of healthcare in Nigeria’s urban slums. Instead of seeing them as part of the problem in the fight against AMR, they should be recognised as strategic partners. Empowering PMVs through knowledge, supportive supervision, and integration into formal health systems aligns with Nigeria’s Health Sector Renewal Investment Initiative, which focuses on health security and quality health systems, as well as global AMR action plans. This approach can fast-track progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC), bolster community-based care, and significantly contribute to national and global targets for controlling AMR and enhancing population health outcomes.

Authors and Bios

Chibuike Agu is a consultant public health physician and senior lecturer at Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Abakaliki, Nigeria. He is dedicated to enhancing healthcare access in underserved Nigerian communities, focusing on neglected tropical diseases, adolescent health, antimicrobial resistance, and strengthening health systems. His public health contributions include leading the development of a strategic plan and a handbook on integrated care for TB, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), and pneumonia.

Ifunanya Clara Agu is a public health researcher specialising in community-embedded studies that target unmet health needs among underserved groups, particularly in Nigeria. She holds a BSc in Public Health and an MSc in Health Promotion and Communication. Currently, she is working on a split-site PhD at the Institute of Public Health, University of Nigeria, and the University of Leeds in the UK, funded by a Commonwealth Scholarship.

Irene Ifeyinwa Eze is a Consultant Public Health Physician and an Associate Professor of Community Medicine/Public Health at Alex Ekwueme Federal University in Abakaliki, Nigeria. She has master’s degrees in Medical Microbiology, Public Health, and Health Policy and Systems. Her research and practical work primarily focus on infectious disease epidemiology, maternal and child health, and strengthening health systems.

Professor Rebecca King is a leading expert in global health and community engagement, based at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom. She heads the Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, where she spearheads research on antimicrobial resistance, participatory health interventions, and applied qualitative methods in low- and middle-income countries.

Professor Chinyere Mbachu is a community health physician, health systems researcher, and Senior Lecturer at the University of Nigeria, Enugu campus. Her expertise includes health policy analysis, systems governance, and the political economy of health reforms. She has contributed to developing curricula in health policy and systems research and has led capacity-building projects for policymakers and practitioners. Her research has influenced strategies for malaria control, improvements in contraceptive access, and accountability in health financing.

Dr. Mahua Das is a Lecturer in International Health at the University of Leeds and oversees the MSc in International Health program. With expertise in Sociology and Social Policy, her research concentrates on community health systems, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Her work emphasises participatory methods in maternal health, sexual and reproductive health, and antimicrobial resistance.

Professor Obinna Onwujekwe is a renowned Nigerian health economist and policy expert. He is the coordinator of the Health Policy Research Group (HPRG) and a Professor at the University of Nigeria, where he leads research in pharmacoeconomics, health systems, and equity. With a medical degree and a PhD in Health Economics from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, he has played key roles in shaping Nigeria’s health financing and policy landscape.

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to Dr Prince Agwu for reviewing this article.