By Obinna Onwujekwe & Prince Agwu

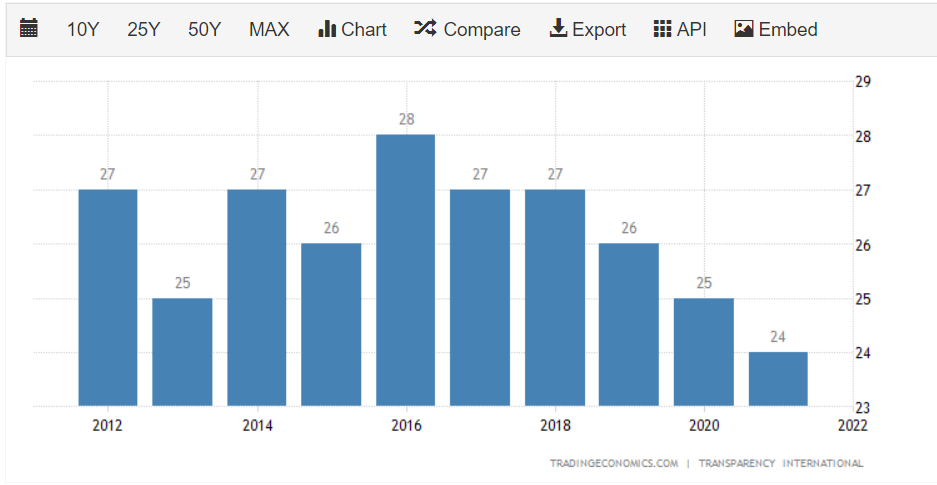

In a previous article of ours, we raised concerns about weak accountability and corruption possibly getting in the way of Nigeria’s response to COVID-19. We cited the report of Transparency International on how corruption affected West Africa’s response to the Ebola epidemic, hoping that the lessons learnt will inform the responses to future pandemics in Nigeria.

There were predictions that the COVID-19 experience will surely not leave Nigeria’s health system in the manner it has always been. Even though the predictions were not clear on if the health system in Nigeria will head in the right or wrong direction. However, the evidence is that the health system is not getting strengthened due to a myriad of factors including poor coordination between the different levels of government, opaque accountability systems, and poorly responsive systems, amongst others.

The accountability mechanisms of these funds are not clear and citizens do not really feel the impact of the resources and there is a seemingly lack of trust in the public sector. This is pertinent because since the pandemic, we have heard on the streets of Nigeria how COVID-19 is a disease for the rich and/or a ploy by the political elites to siphon funds as it is considered customary to them. What we have seen is the outright discard of measures to stem the spread of coronavirus, as the average Nigerian seems to have rather given up on the government, but more concerned about their daily economic survival. We saw how this played out during lockdown, with Nigerians conniving with the Police to defy government directives to stay at home and even threatened to protest continued lockdown after an initial extension.

Now, easing the lockdown has seen a surge in coronavirus cases and deaths, difficulty to contact-trace, few citizens tested, and life seems to have returned to normal, yet Nigerians are largely unbothered. The question is, do we blame Nigerians for taking such position of survival and carelessness at the same time? Elizabeth Donelly of the Chatham House importantly and emphatically said that citizens’ trust is key if the Nigerian government must tackle COVID-19. But with emerging revelations of corruption and weak accountability, the question about trust is answered by the current defiant actions of citizens which seem to compromise responses to containing the virus, as well as the rage and piling of court cases spearheaded by Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) against the government within this time.

For a start, the primary healthcare (PHC) system seems to have been hardly involved in the fight against COVID-19. The scare of the virus has rather inspired low patronage, with concerns for Universal Health Coverage. This is in contrast to the active roles of the primary healthcare in Rwanda, Cuba and Thailand. What rather happened in Nigeria was a massive slash of the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund expected to revamp primary healthcare, which is direly needed during a pandemic as this one, as against a smaller cut in the appropriation meant to renovate the National Assembly Complex.

At a time when countries are making conscious efforts to spend in health, and particularly, human resources for health, health workers in Nigeria have severally indulged or threatened to indulge industrial actions within this time, protesting against neglect and failed promises. Yet at the same time, a single commission in the country shared over N3bn as COVID-19 relief funds among its staff, and federal-level legislators reportedly took delivery of 400 exotic cars at a price of over $20,000 for each.

Since the onset of the pandemic, the Federal and State governments of Nigeria have received cash and kind donations from both private and public donors, of which the cash component alone exceeds NGN230 billion[1]. At the same time, the FGoN’s 2020 health budget was increased by more than 13% from the previous year’s budget[2]. Additional resources that were mobilized include $12 million donated by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) for health worker training, commodities supplies, surveillance, communication and coordination, etc[3]; some of the over NGN 30 billion raised by the Coalition Against COVID-19 (CACOVID)[4]; and 100 million grant from the World Bank to each state.

Of keen interest to Nigerians, are donations made to the government in the fight against COVID-19. At some point, citizens were worried about making such donations to a government they do not trust, rather than channelling directly to the poor and less privileged who are littered all over the country. In later events after the country moved into a post-lockdown, citizens were seen breaking into warehouses to cart away donated palliatives (food items) mainly from the private sector. The citizens expressed shock and disappointment at the much quantity of items that were allegedly hoarded by the leaders, even as they have been faced with harsh economic impacts from Covid-19 all the while.

[1] https://civichive.org/covidtracka/donations/

[2] https://yourbudgit.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2020-Budget-Analysis.pdf

[3] https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/Gavi-COVID-19-Situation-Report-15-20200811.pdf

[4] https://www.cacovid.org/pdf/list_of_contributors_to_the_cacovid_relief_fund_as_at_30_June_2020.pdf

The news of distrust, corruption and weak accountability have been rife in Nigeria within this time. From the distribution of N20,000 cash to some 2.6m poor Nigerians in 10 days, and the feeding of pupils in lockdown with N500m, all seem to have raised serious concerns about accountability, thus, seeming to confirm the fears of Nigerians. Heightened distrust about spending from the Humanitarian Ministry forced the National Assembly to call the Ministry to explain the figures they have in the public domain, including the steps they took to identify poor Nigerians who benefitted from the palliatives. Despite interventions from the National Assembly and public concerns, little or nothing is done to effectively open up activities of the Ministry to public scrutiny.

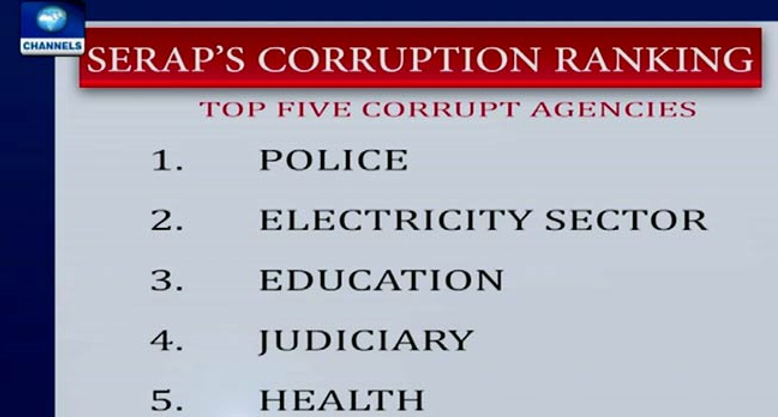

A cesspool of corruption in Nigeria is procurement. It reflects the saying by Patricia Garcia “with more money comes more corruption”. One might want to believe that Patricia made the statement with Nigeria in mind. COVID-19 brought about the need to procure certain items in bulk, particularly facemasks, hand sanitizers, disinfectants, among other personal protective equipment. At the onset of the pandemic, most of these items were in short supply, and the compulsory need for them led to increased spending in that direction. Expectedly, a hub for corruption seems to have emerged.

The Open Treasury Portal which government built to feed Nigerians information concerning COVID-19 funds appears to be a work-in-progress, as some important pages do not open. It as well does not give any detail concerning procurement, rather it provides information on bank transactions which amount to insufficient. There is also the CovidFundTracka which only spells out what is donated to the country but not what is spent. Although there is a guideline for COVID-19 procurement as published by the Bureau of Public Procurement, the document seems more rhetoric than action.

Consequently, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) try to ask questions and monitor government spending, of which the revelations of possible corruption have been quite revealing. The Ministry of Health is implicated in the purchase of facemasks for about N20,000 ($52) per one and awarding of supply contracts without evidence of competition and bidding. The Federal Road Safety Commission was equally said to have purchased a bottle of 500ml of hand sanitizer for N5,600 ($14) as against the most expensive cost price of N3,000 ($7). Many public agencies in both within and outside the health sector have all been implicated in the possible poor procurement practices in the fight against COVID-19.

If there is a time Nigerians expect transparency and accountability from the various government Ministries, Departments and Agancies that are involved in the COVID-19 response, it is now. The pandemic places moral responsibilities on governments to get concerned with the affairs of citizens and not further create conditions that will escalate distrust. Nigerian government across all levels should see to it that they win back the trust of citizens by an application of the “rule of law”, and not “rule by law” which has largely been the case. A lot depends on the trust of citizens in their government during disease outbreaks, particularly concerning community engagement, resilience and effective response. These are areas where Nigeria keeps lacking. No doubt that trust is key to reviving these cardinal areas in disease response. It is hoped that Nigeria learns and at least puts forward a sincere, transparent and corruption-free approach in addressing the pandemic onward.

=====

Obinna Onwujekwe is a Professor of Health Economics, Systems and Policies in the University of Nigeria Enugu Campus. He is the Chief Editor of the African Journal of Health Economics, and the Coordinator of the Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria. He coordinates the African Health Observatory Platform (AHOP) for Health Systems, Nigerian Center.

Prince Agwu is an academic in the Department of Social Work, University of Nigeria and a research associate in the Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria.

L-R front row: Dr John Onyeokoro (Health Watch Resources Ltd); Prof Muktar Gadanya (BUK); Prof Chinyere Mbachu (HPRG); Prof Isa Abubakar (BUK); Prof Ekanem Braide (NAS); Dr Idris Muhammad (Health Reform Foundation and Chair, HAPAC); Victoria Bamas (ICIR); Iyanuoluwa Bolarinwa (BUDGIT)

L-R front row: Dr John Onyeokoro (Health Watch Resources Ltd); Prof Muktar Gadanya (BUK); Prof Chinyere Mbachu (HPRG); Prof Isa Abubakar (BUK); Prof Ekanem Braide (NAS); Dr Idris Muhammad (Health Reform Foundation and Chair, HAPAC); Victoria Bamas (ICIR); Iyanuoluwa Bolarinwa (BUDGIT)