More than half of Nigeria’s over 200 million population are under the age of 18, and just about 29 percent of the over 100 million Nigerian children are under 5 years. Children between the ages of 5 and 17 comprise the larger share of Nigeria’s children population but are least catered to by the Nigeria’s health system that is more interested in the under-5s. As such, health rights of children between 5 and 17 years have remained threatened, calling for urgent attention.

Supporting our assertion above is the evidence of demarcation between under-5 and school-aged children (5 – 17 years) in Nigeria’s National Health Policy but the listing of child-health-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for under-5s alone. Similarly, the guideline for the implementation of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) recognises just under-5s as among the five vulnerable groups, again, leaving out children between 5 and 17 years.

Understandably, policies like the 2003 Child’s Rights Act (CRA), 2006 National School Health Policy (NSHP), 2019 National Policy on the Health and Development of Adolescents and Young People (NPHDAYP), and 2022 National Child Health Policy (NCHP), have made attempts to recognise the uniqueness of children aged 5 – 17 years and the need to dedicate special care to their health and health rights. However, academic assessments and other significant evaluations of these policies have shown that they have not been strategic enough or well-implemented to provide sufficient protection for school-aged children’s health and health rights. Unsurprisingly, the Nigeria’s National Development Plan (2021 – 2025) decried poor enforcement of children’s rights laws and the absence of children’s viewpoints in health policymaking/enforcement.

Indeed, Nigeria may not have come to terms with the significant harm this lack of intentionality towards the health and health rights of school-aged children has caused. This was revealed in a recent research conducted by the Health Policy Research Group – University of Nigeria and the School of Humanities & Social Sciences/Law, University of Dundee, under the CHORUS Urban Health Consortium, with support from the Rivers State Ministry of Health. As national and subnational level stakeholders in health, education, social welfare, and human rights fields, drawn from 24 ministries, agencies, and organisations in Nigeria, we have gone through the study, validated the data, and have come up with our position. But first, we present a summary of the research evidence.

Evidence from the research

Four levels of research inquiries involving document reviews, in-class observations of children, and interviews and policy dialogue with a broad collection of national/subnational stakeholders inclusive of children, caregivers, teachers, school owners, attorneys, and policymakers were applied to gather evidence on (1) the policy environment for the protection and promotion of the health and health rights of school-aged children (2) patterns of seeking healthcare for school-aged children, and (3) threats to the rights of school-aged children to quality, safe, and timely healthcare. The research was focused on urban settlements in Rivers State, inclusive of urban slums. Across the three areas of inquiries, the study found that:

- Policies and laws expected to protect and promote the health and health rights of school-aged children failed several set expectations when judged against evidence from academic investigations and other significant inquiries. Notably, the 2006 National School Health Policy designed to play a pivotal role in supporting other related policies, has largely failed in its implementation. Conflicts in the leadership of the School Health Policy undermined its implementation progress and significantly contributed to the isolation of schools away from the health system, especially primary healthcare.

- Health seeking for school-aged children largely defied the provisions of safety and quality in the Child’s Rights Act [CRA]. The dominant health-seeking routes were home management of illnesses using self-prescribed medications; drugs bought from drug vendors or self-mixed herbal remedies; herbal practitioners’ recommendations, and solicitation of spiritual interventions from religious clerics even at critical times. The significance of primary healthcare was hardly recognised, as many rather jumped to private clinics or secondary/tertiary facilities when prior self-help and informal arrangements failed them.

- The school-aged children decried the absence of health personnel and health facilities in their schools. More so, they complained about the absence of a responsive care and reporting system to either discuss their physical and mental health needs or to report risky health options and behaviours stimulated and encouraged by their caregivers. The children equally recognised inefficiencies and unsupportiveness of health facilities, particularly the unruly attitudes of health workers toward children and their caregivers, high fees for health services, poor emergency response to children in health crises, and constrained physical access to health facilities.

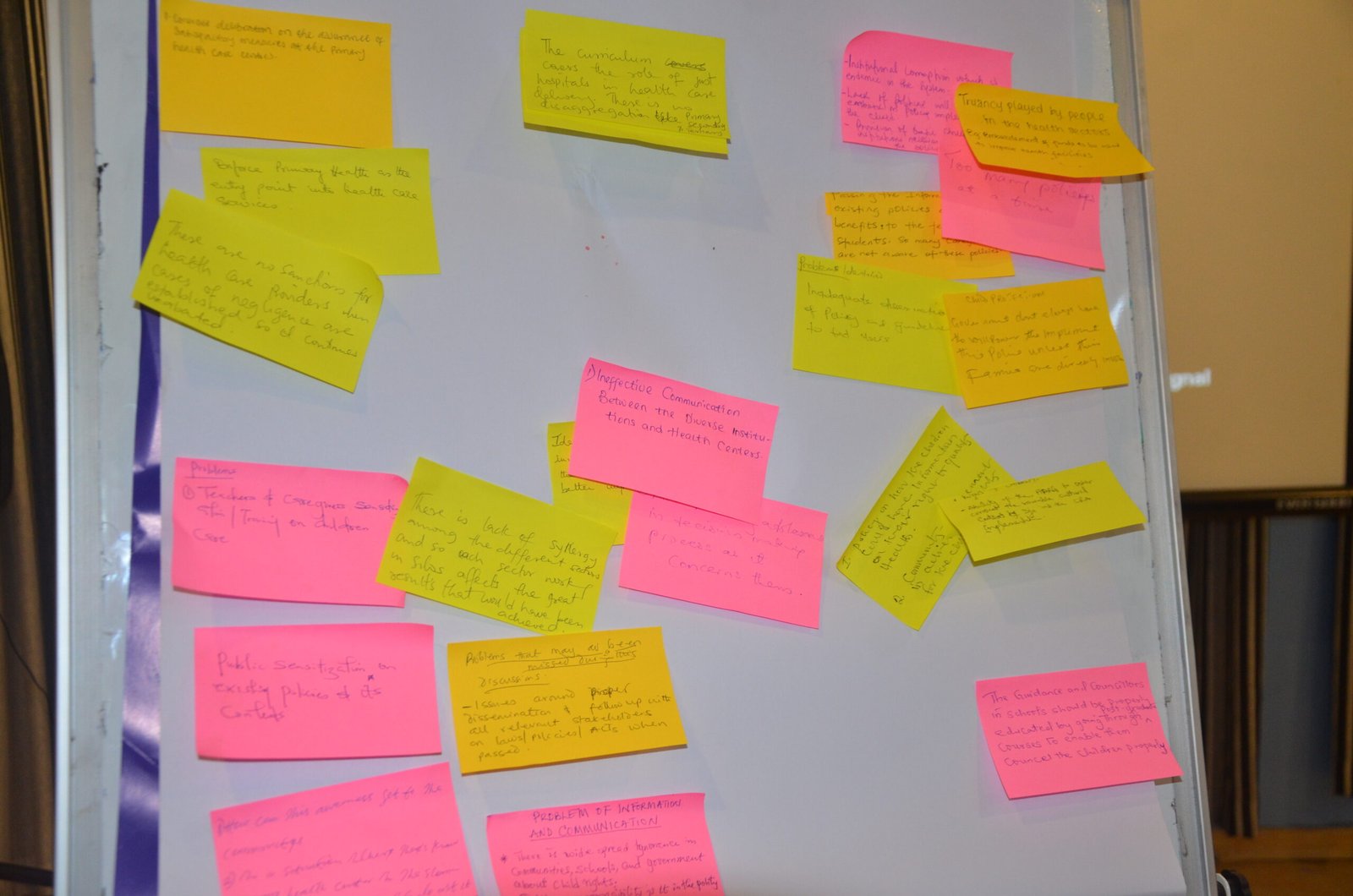

Policymakers and other stakeholders validate evidence and prioritize actions

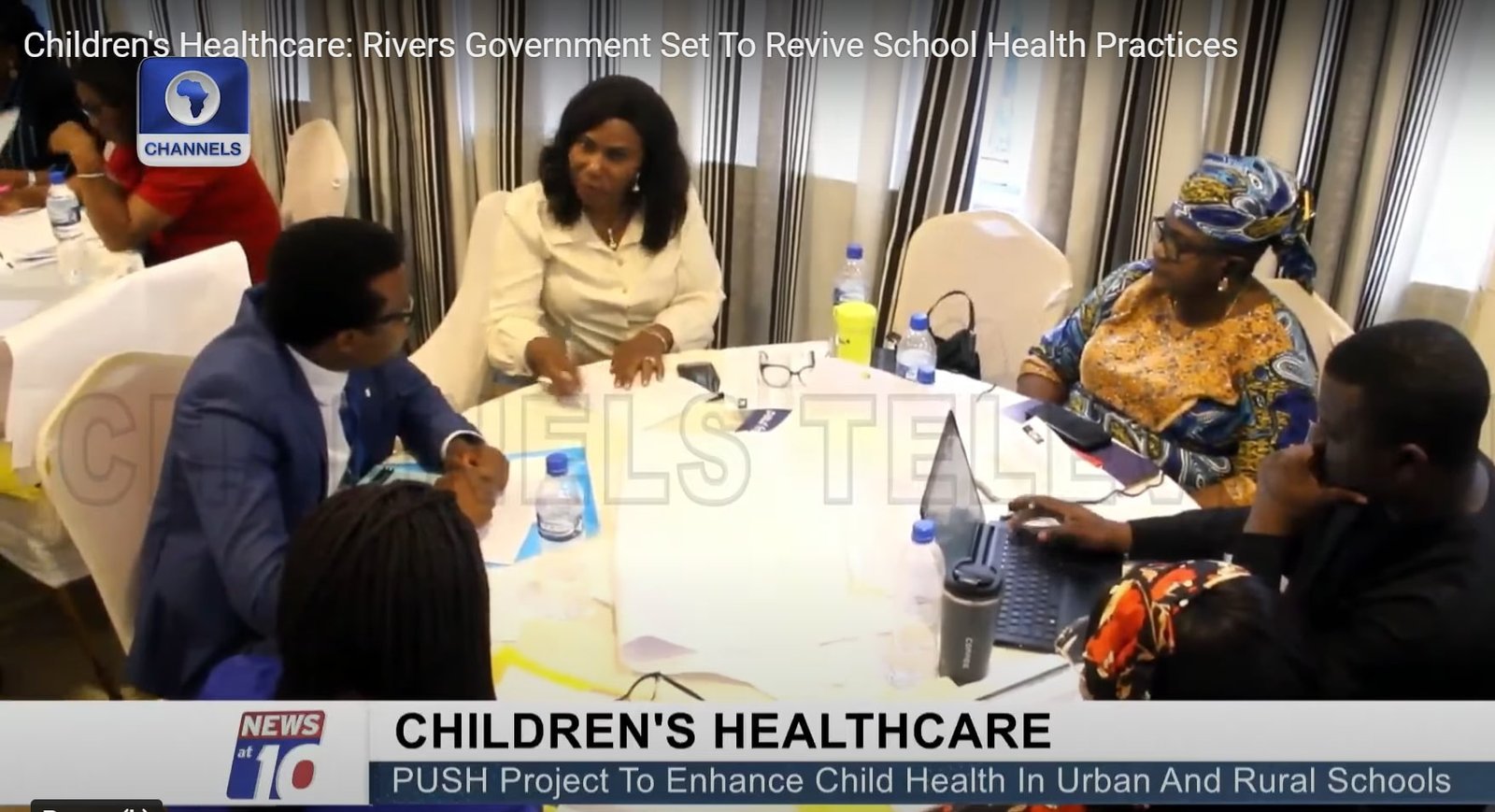

On August 5 and 6, 2024, stakeholders met in Port-Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria, and without reservations we commended the now nationally accepted and domesticated CRA across the country’s federating units. We also appreciated the working groups for adolescents’ health based on the emergence of health programmes for adolescents and the progressive scaling of adolescent-friendly health centres. And importantly, we hailed the ongoing health systems strengthening blueprint that recognises the centrality of school health services to the health needs of school-aged children.

Notwithstanding these commendable efforts, we pointed out fifty-one concerns which we later condensed to five specific areas using a Modified Delphi Technique to deliberate and consensually rank priorities. Our agreed five areas and suggested actions for governments at all levels are:

- Leads of the health, education, and social welfare (women affairs in some cases) ministries must leverage current evidence for the review of school health-related policies with the aims of: (a) harmonization of contents (b) setting very feasible targets with realistic benchmarks to gauge progress, and (c) reaching a definitive consensus on the leadership of school health with clear definition of roles and responsibilities.

- Leads of the health, education, and social welfare ministries should work with the legislative committee on health, the criminal justice system, children’s parliament, and the child’s rights implementation committees to design and enforce clear and widely communicated standard operating procedures for reporting and responding to actions that violate the rights of school-aged children to safe, quality, and timely healthcare.

- The above actors should work with the national orientation agency, academia, civil society organisations, community-based organisations, children’s parliament, and media to design a simplified and effective communication framework for the harmonized policy contents and standard operating procedures which must include: (a) mainstream into school curriculums (b) pasted prints in health facilities and schools (c) repeated announcements in religious gatherings, and (d) unrestricted digitized accessibility.

- The lead of the state health ministry should work with the primary healthcare development agency, health insurance agency, and the education ministry to: (a) design schools’ clusters around designated functional primary health facilities with school health desks headed by appointed school health desk officers (b) encourage appointments of school health focal persons to link schools with the designated health facilities (c) design terms of reference and workflow modalities (d) explore inclusion of school-aged children in the basic healthcare provision fund, and (e) nudge schools toward employing at least one qualified health personnel and setting up equipped sickbays in the long-run.

- The consensually agreed leadership of school health will explore external funding while compulsorily including school health services in the annual operation plans and budgets to cover funding the desk offices, enforcement of the standard operating procedures, and all other health systems and wider responses to the health and health rights of school-aged children.

Our conclusive position

As stakeholders, we acknowledge the fragility of the under-5 population, hence the enormous attention accorded to their health needs, and we encourage even more. However, it is worrisome that the bulk of the country’s population between the ages of 5 and 17 years who are also children have not received as much attention as they deserve health-wise. The consequences are regrettable, evidenced by gross violation of their health rights, poor institutional responses to their health needs and rights, and avoidable cases of morbidities and mortalities.

As stakeholders from different fields, we underscore the need for a more coordinated, strategic, and inclusive approach to health policymaking that prioritizes the unique needs of school-aged children. This should begin with reviewing and implementing an effective school-health or holistic child-health policy that prioritises the health rights of school-aged children, school-health services, and easily accessible primary healthcare services for school-aged children. It should be supported by widely communicated and accessible deterrence mechanisms to put an end to the violation of the health rights of school-aged children in Nigeria. By adopting a more holistic and intentional focus on the health rights of school-aged children, Nigeria can make progress towards ensuring that all children, regardless of age, have access to safe, quality, and timely healthcare.

Acknowledgement

- Rivers State Ministry of Health

- Rivers State Ministry of Education

- Rivers State Ministry of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation

- Federal Ministry of Health (Family Health Department/Child Health Division)

- Federal Ministry of Education

- Federal Ministry of Women Affairs

- National Primary Health Care Development Agency

- Rivers State Primary Healthcare Management Board

- National Health Insurance Authority, Rivers State

- Rivers State Adolescent Technical Working Group

- National Child Rights Implementation Committee

- Rivers State Family Court

- Aret and Bret LLP Law Firm

- Results for Development, Nigeria

- Marine Base Community

- Assemblies of God Church, Amadi-Ama, Rivers State

- Police Station Mini-Okoro Mosque

- The Boy Child Support Network

- Rhema Care

- Channels TV

- Wish FM

- Model Senior Secondary School, Rivers State

- Pneuma Citadel Academy, Rivers State

- Dr Tarry Asoka (Independent Health Consultant)

- UNICEF, Rivers State Field Office

- CHORUS Urban Health Research Consortium

- University of Dundee, United Kingdom

- Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria

Research Team (L-R): Ifunanya Agu (Project Manager), Dr Aloysius Odii (Research Associate), Prof Uzoma Okoye (Research Co-Lead), Dr Adaeze Oreh (Hon. Commissioner for Health, Rivers State, Nigeria), Dr Prince Agwu (Research Lead), Chinelo Obi (Research Associate)

Correspondence: prince.agwu@unn.edu.ng

Click to download the communique in pdf

Photo Gallery