Following a two-year study on healthcare/health rights for school-aged children (5 to 17 years) and school health services in urban settlements in Nigeria, significant concerns have been raised regarding the health and safety of school children. The study was conducted by researchers from the Health Policy Research Group (HPRG) at the University of Nigeria and the Education & Society Division at the University of Dundee in the United Kingdom, in partnership with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the Rivers State Ministry of Health, and the Community-led Responsive and Effective Urban Health Systems (CHORUS).

Findings from the study led to two policy dialogues on the health of school-aged children and school health services. This communiqué reports the consensus reached during the national policy dialogue (April 9 and 10, 2025) across themes of: (a) context of child/school health (b) discussions of evidence from the child/school health study, (c) resolutions based on the evidence, and (d) conclusive position of stakeholders on the ways forward for school health.

Context: Nigeria’s child health laws/legislation fail 70% of its child population

- Despite school-aged children (ages 5 – 17) making up 70% of Nigeria’s child demographic, their health needs remain largely unmet. When ‘child health’ is discussed in Nigeria, it typically pertains only to those under five years old. As a result, the overall performance regarding health outcomes, health rights, and child protection for this age group is among the worst in the world. Specifically, Nigeria holds the 174th position out of 180 on the Child Flourishing Index, ranks 182nd out of 194 on the KidsRights Index, and sees a staggering 125.66 deaths per 100,000 adolescents, in contrast to 12 deaths in Europe and 45 in Asia.

- Health assessment scores for Nigerian children aged 5 to 17 indicate that the country has inadequately protected the health and rights of this vulnerable population. This underscores the shortcomings of our legislation and policies, including the Child’s Rights Act [CRA, 2003], National School Health Policy [NSHP, 2006], National Policy on the Health and Development of Adolescents and Young People in Nigeria [NPHDAYP, 2019], and National Child Health Policy [NCHP, 2022]. Thus, while reviewing obsolete policies (e.g., NSHP) is imperative, we must explore innovative approaches to strengthen enforcement, ensuring that children and families in Nigerian communities benefit from existing child/school health laws and policies.

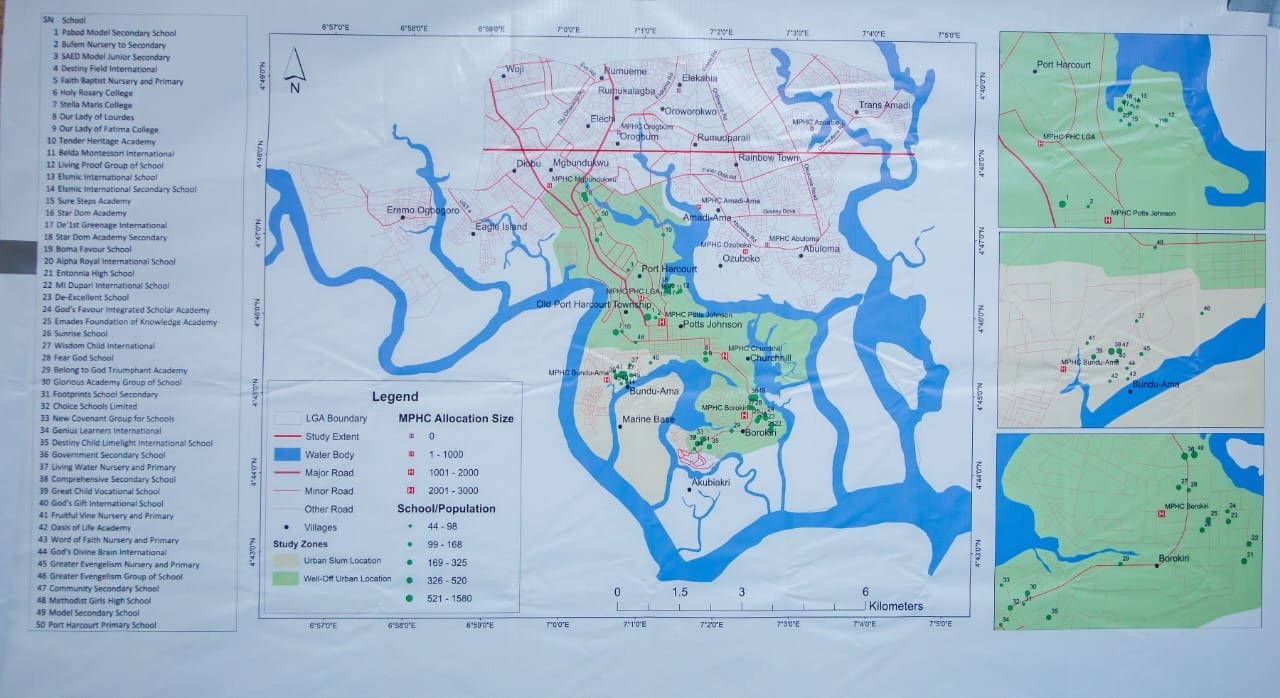

- To initiate efforts to create a safe health environment for school-aged children, our study has led to two policy dialogues conducted at different times—one in Rivers State (August 2024) and the other in Abuja (April 2025). These dialogues were informed by substantial research evidence, consisting of approximately 1000 direct engagements with relevant stakeholders, including children, through interviews, group discussions, surveys, classroom observations, and geographical information system (GIS). Therefore, we take pride in the quality of the evidence guiding this entire process.

Discussions: Stakeholders lament poor school health, believe that “health and well-being for school children is the most viable pathway to child protection for the Nigerian child”

- As stakeholders gathered at this policy dialogue, we affirm that the study’s evidence accurately reflects the health conditions in schools, marked by the lack of in-school health services, inadequate and poor healthcare practices by school staff risking the safety of school children, insufficient formal health oversight in schools, and the unavailability of healthcare referral options for school children. Consequently, numerous health and wellbeing threats to school children are ignored or inadequately addressed.

It is troubling that many schools are unaware of the roles played by primary healthcare centres (PHCs) in promoting school health. As a result, schools have established links with informal health providers, including patent medicine vendors (PMVs) and unlicensed drug shops, despite well-functioning primary healthcare centres (PHCs) close to them. Unfortunately, the repercussions for school children have been significant, including fatal outcomes. We agree with the study’s finding that there is a widespread deficiency in child protection within our schools, which must be addressed by devolving relevant policy measures to the frontline. Prioritising the health and well-being of school children via school health services is the best way to drive this change. We believe this will also benefit other community structures, such as families and places of worship. - We express our frustration with the operational plans of public and private schools, which largely lack provisions for in-school health services. Regrettably, altering this situation may now prove challenging due to the escalating costs of running public and private schools amidst the country’s broader economic difficulties. Therefore, we require innovative strategies to ensure our schools support health and adhere to child protection standards. We outline these strategies in the next section.

- Throughout the series of engagements, five crucial areas have surfaced as vital for reimagining and rejuvenating school health to improve health outcomes for school children in Nigeria. These areas are: (a) fostering inter-ministerial cooperation among relevant ministries for school health, with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, (b) effectively integrating schools with the primary healthcare system, (c) reviewing and aligning the National School Health Policy (NSHP), (d) creating dedicated and innovative funding mechanisms for school health, and (e) explicitly communicating penalties for actions that violate the health rights of any child.

As a collective, we have initiated transparent and candid discussions regarding these five key areas. They are addressed in the next section in light of the urgent need for practical actions to enhance and safeguard the health and well-being of school children in Nigeria.

Resolutions: five strategies for reimagining and rejuvenating school health

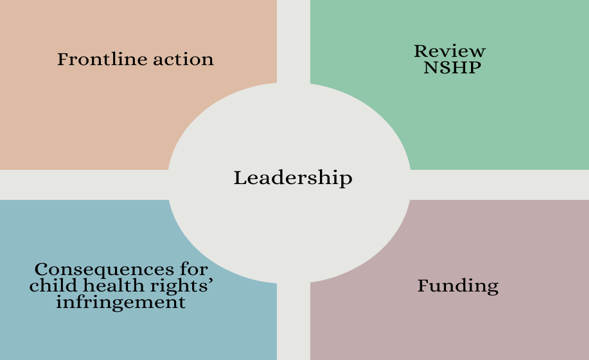

We have reached a consensus on the five strategies for reimagining and rejuvenating school health, which include: leadership, frontline action, reviewing the NSHP, funding, and consequences for infringements of children’s health rights.

- Leadership: We believe the Child’s Rights Act clearly emphasises the duty of the relevant authorities responsible for child protection to ensure that every child achieves optimal health. After examining the content of the NSHP and considering the evidence from this research, we advocate for a shared leadership approach in the NSHP, partnering with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Both Ministries must critically assess their roles based on their comparative advantages and legal responsibilities.

Also, the Ministry of Women Affairs, whose legal roles include formulating and implementing child rights and protection policies in Nigeria, must participate in the leadership setup. This should be followed by effectively incorporating the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) and its state-level counterparts. School health services are part of the minimum service package to be delivered by primary healthcare in Nigeria, and the NSHP and NCHP equally affirm this. Additionally, to invigorate school health and prioritise it as a national development goal, it is essential for the Ministry of Budget and Economic Planning to prominently feature “School Health” in the upcoming National Development Plan. - Frontline action: We have established that the disconnect between schools and the primary health system constitutes a clear violation of our child rights laws and child health legislation, namely the CRA, NSHP, NPHDAYP, and NCHP. These laws and policies explicitly mandate the comprehensive integration of all child health services into the primary healthcare system. With this understanding, we have collected empirical evidence, including geographical assessments through the GIS, which endorses connecting school clusters with PHCs. We agree that the School Health Desk Office (SHDO), typically based at the State Primary Healthcare Agency level, can only function effectively with intentional decentralization efforts. Thus, we strongly recommend establishing a School Health Unit (SHU) within the relevant PHCs to oversee designated school clusters, paying attention to the population of pupils per cluster to avoid over-clustering.

Additionally, schools should designate trained health focal persons to act as liaisons between themselves and the SHUs. This step is crucial to stimulate frontline actions aimed at fulfilling the objectives of the School Health Policy and promoting child protection more broadly. We are finalising a protocol to regulate SHU operations and practices, addressing governance, financing, human resources, information systems, and service delivery. This protocol will also outline guidelines for referrals from PHCs to higher-level facilities when necessary, and emphasise the importance of governing informal health providers, such as Patent Medicine Vendors, operating within these clusters. We will hand in the protocol to the NSHP leadership structure. - Review NSHP: The National School Health Policy (NSHP) is outdated and requires a thorough review. Our analysis highlights critical areas needing attention in this review process. Firstly, the NSHP’s overall vision should align with contemporary global and national health and child protection priorities, particularly the health-promoting school initiative supported by the health and child sectors of the United Nations. Secondly, the policy’s strategic elements must clearly define the range and types of services provided under school health, work with evidence-based models to sustainably deliver these services, outline the active involvement of children in implementing the policy, clarify the distinct responsibilities of relevant ministries and agencies, designate technical workgroups, and establish financing mechanisms that depend on government funding, innovative sourcing, and private sector involvement.

Thirdly, realistic key indicators for measuring the policy’s progress should be established, with evidence-based and locally led frameworks for monitoring. Fourthly, the revised NSHP should include legal frameworks establishing and regulating school health units (SHUs), reiterating children’s health rights, and defining the penalties associated with violations. Fifthly, priority should be given to equity and inclusion issues, such as special provisions for children with disabilities, orphans, and those living in urban slums. Lastly, efforts must be made to ensure that the NSHP is well-publicised and included in school curricula as part of civic education. Research indicates that more than 60% of secondary school teachers are unfamiliar with the NSHP, which obviously reflects worse awareness scenarios among children and caregivers. - Funding: The ongoing Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) provides an opportunity to fund school health initiatives. We strongly advocate for granting school children vulnerability status, enabling them to access Vulnerable Group Fund (VGF) support. This initiative could be phased in, starting with public school children or children living in poverty. Furthermore, we suggest conducting an actuarial cost analysis to determine the most feasible premiums for school children. School Health Units (SHUs) require funding, and in addition to appropriations from the government, we believe they could also receive funds from donors and the private sector if well-positioned.

- Consequences for child health rights’ infringement: In Nigeria, the child protection landscape is quite inadequate, mainly due to the ongoing violations of children’s rights, including their health rights, without any significant penalties enforced. We are concerned that these violations and associated penalties are largely unfamiliar to the public. Therefore, we appreciate the initiative proposed by President Bola Tinubu to establish a specific Child Protection and Development Agency. However, this effort still requires proactive agents on the frontline, which the proposed SHUs embody perfectly. We are confident that through this grassroots framework (the SHUs), the specifics of violations against children’s health and well-being can become ingrained within local communities, which is the most significant step to take in enforcing child protection nationwide.

Our conclusive position

- Approximately 70% of Nigeria’s children face risks to their wellbeing and health due to inadequate enforcement of existing child health legislation and the outdated NSHP. Nigeria’s health system has centred mainly on children under five (0-4 years), leading to this age group being viewed as the standard for children. This oversight of school-aged children (ages 5-17) is troubling, as it exacerbates the poor child protection and health outcomes Nigeria experiences on a global scale. To address this issue, schools must become the focus, given their crucial roles in education and daily child management for approximately nine months each year. Thus, it’s vital to rethink and revitalise school health services in Nigeria.

An urgent review of the NSHP is necessary to ensure it effectively promotes actions that enhance the health and wellbeing of children. We have pinpointed key areas for this review while strongly urging connecting schools with the primary health system. This linkage should involve transferring the management of school health services to School Health Units (SHUs) housed in primary health facilities to supervise school clusters. As we work to finalise the protocol for the SHUs, we have suggested initial steps to kickstart this process. We will keep collaborating with relevant authorities until we are confident that every Nigerian child receives the support they need for optimal health and wellbeing.

Participating organisations

- Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria

- Rivers State Ministry of Health, Nigeria

- CHORUS Urban Health Consortium

- Education & Society Division, University of Dundee

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- Rivers State Ministry of Education, Nigeria

- Rivers State Ministry of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation, Nigeria

- Rivers State Primary Health Care Management Board, Nigeria

- Rivers State Contributory Health Protection Programme, Nigeria

- Rivers State Ministry of Justice, Nigeria

- Rivers State Family Court, Nigeria

- Federal Ministry of Health (Family Health Dept/Child Health Division), Nigeria

- Federal Ministry of Education, Nigeria

- Federal Ministry of Women Affairs (Child Development Department), Nigeria

- Federal Ministry of Budget & Economic Planning, Nigeria

- Federal Ministry of Information and National Orientation, Nigeria

- National Health Insurance Authority, Nigeria

- National Primary Health Care Development Agency

- Federal Ministry of Justice, Nigeria

- Sector-Wide Approach Coordinating Office (SWAp), Nigeria

- Children’s Parliament, Nigeria

- Federal Capital Territory Health Services & Environment Secretariat

- Results for Development, Nigeria

- Assemblies of God Church, Rivers State, Nigeria

- National Assembly Mosque, Abuja, Nigeria

- Oakdale International School, Rivers State, Nigeria

- Aret and Bret LLP Law Firm

- Voice of Nigeria

- International Centre for Investigative Reporting, Nigeria

- The Guardian, Nigeria

- Leadership News, Nigeria

L-R (sitting): Prof. Uzoma Okoye, Dr Prince Agwu, Dr Adaeze Oreh, Prof. Chinyere Mbachu, Dr Tarry Asoka

L-R (standing): Ifunanya Agu, Chinelo Chieze, Chinemelu Ndichie, Chinelo Obi, Onochie Eze, Dr Aloysius Odii

Team members not in photo: Prof. Obinna Onwujekwe (Coordinator, HPRG), Ass. Prof Eleanor Hutchinson (LSHTM), & Dr Charles Orjiakor

Download pdf version of the communique

News Publications

The Guardian – https://guardian.ng/news/experts-make-case-to-reverse-gap-in-healthcare-for-schoolchildren/

Leadership – https://leadership.ng/stakeholders-seek-health-rights-for-schoolchildren-under-push-initiative/

Contact: Dr Prince Agwu (Principal Investigator)

Email: prince.agwu@unn.edu.ng

Cc: Ifunanya Agu (Project Manager) ifreda198@gmail.com

Photo Gallery