December 2024

The Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria (HPRG) has stayed optimistic about the ‘renewed hope’ agenda for Nigeria’s health sector. Our 2023 health sector roundup hailed the Health Sector Renewal Investment Initiative (HSRII) as timely and well-positioned to radically improve the country’s health sector if well-funded and aggressively implemented. In a year now, our optimism has been energized by the subsequent operationalization of the HSRII in Nigeria’s Health Sector Strategic Blueprint (HSSB) and the rallying of diverse health sector strategies around the HSRII. There is no doubt that this clear vision for the health sector in Nigeria is commendable.

As one of Africa’s frontline health systems research evidence hubs, and in operation for over two decades, HPRG remains committed to evidence generation and application to health policies, strategies, and programmes. In the 2023 roundup, we used evidence to define some important pathways for the health sector in 2024, encompassing five areas listed in the image below.

This year’s roundup looks at the sector’s progress for 2024 based on the pathways listed above. Our thoughts and analyses are driven entirely by data from our cutting-edge studies.

(a) The use of evidence for health policy and systems strengthening

Although the evidence-to-policy space remains wide, we reckon deliberate efforts by the current health administration to fill the gaps. We have observed progress in the use of evidence to build the accountability framework for the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF); the viability of the Research Knowledge and Management Division (RKMD) at the Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (FMoHSW); the Joint Annual Review (JAR) of the health sector; evidence-use as part of the criteria for the national primary healthcare leadership award; rapid digitalization of health services and data, and health policymakers engaging evidence-led policy dialogues and symposia.

However, the full potential of the RKMD to serve as a national health research hub is yet to be realised. There are expectations for the RKMD to focus on timely retrieval, synthesis, consolidation, and communication of a range of health research in the country, including leading evidence-based conversations at the National Council on Health (NCH). Also, the HSRII pillars would benefit from clearly including health policy and systems research (HPSR).

In the same context of evidence-use, Nigeria faces a pivotal moment in its history as the Global Alliance prepares to transition funding responsibilities to countries. Nigeria already recognises this shift, owing to the topicality of vaccine financing in most national health discourses. It has become crucial that Nigeria must prioritize the most impactful vaccines at the best cost. To help with this, HPRG has championed initiatives like Health Technology Assessment (HTA), cost-effectiveness analyses, and localized quality-of-life value sets. These efforts are aiming to ensure sustainable and evidence-based decision-making tailored to local needs for vaccines.

(b) Aggressively pruning informal health spaces

Informal health providers (IHPs) like Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs), Patent Medicine Vendors (PMVs), Traditional Bone Setters (TBS), etc., have proven useful to Nigeria’s under-resourced healthcare space. However, they constitute enormous threats to care quality.

At the 65th NCH, concerns were raised about the continuous patronage of TBAs over skilled birth attendants, likewise normative patronage of PMVs. HPRG is working on a linkage system between IHPs and the formal health system. Findings from our interventive study document the aspirations of community stakeholders to provide more formal oversight to the activities of IHPs, and IHPs showing willingness to get linked to the formal health system. In one of our published studies, just about 7% of 238 IHPs could identify risk factors and symptoms of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. And we can authoritatively report many ungoverned spaces among IHPs.

Efforts outlined at the 65th NCH and JAR in engaging TBAs as referral sources, deploying primary healthcare service protocol to Community Pharmacists and PMVs, strengthening the Community Health Influencers and Promoters (CHIPs) and revamping primary healthcare facilities make a lot of sense. But these efforts should extend to the bone setters and herbal practitioners, and overall, should rely on ‘proof-of-concept’ manuals, protocols, and practices – HPRG is always willing to share its intervention experiences with health authorities.

(c) Focusing on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) needs of school-aged children, adolescents, young people, and other vulnerable groups

The expansion of the Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (RMNCH) to cover Adolescent and Elderly Health (RMNCAEH) is commendable. The design and adoption of a national strategy for it, including the clinical protocol for adolescent health services is laudable. However, we are deeply concerned about the readiness of our primary health centres (PHCs), schools, and communities to key into delivering the visions and objectives of these several policy documents and guidance.

Our concerns stem from the incomprehensive staffing of PHCs that are often without laboratory diagnostic and social care professionals; PHC workers usually adhering to rigid gender norms that result in judgemental attitudes and discriminatory practices that negatively impact adolescents and young people’s access to SRHR services; the poor orientation of mental health services and adolescents’ care needs among communities, and the absence of school-based health services.

In response to these concerns, we have undertaken several past and ongoing initiatives including the development of manuals, job aids and training programmes for PHC workers. These efforts aim to enhance the provision of youth-friendly SRHR services through gender-transformative and intersectional approaches in PHCs, and communities.

Close to adolescents are school-aged children who are 5 years and above. There is evidence that this population group, although vulnerable, do not get the attention they deserve. The poor implementation of the Child’s Rights Act and the conflict between the Ministries of Education and Health have hampered the implementation of the National School Health Policy. Sadly, many children in Nigeria are not covered by structured health programmes, and they continue to be victims of poor health-seeking practices obtainable within their homes and communities, with no one in their defence.

While it is important to address the policy framing and leadership of school health alongside the aggressive implementation of the health components of the Child’s Rights Act, HPRG is strategically clustering schools around functional PHCs using Geographic Information System (GIS). This is expected to re-envision the school-based health services and enhance health protection for Nigerian children who are 5 years and above, including adolescents.

Contingent on the foregoing, the definition of vulnerable people as contained in the listing of those who qualify for the Vulnerable Group Fund (VGF) under the BHCPF, may benefit from contextual subnational flexibilities. For instance, our work in Edo State found grave health challenges facing survivors of human trafficking, yet the health system is completely disconnected from their realities. And some health challenges faced by the elderly may rather need social care. The ideals for which the VGF was designed to achieve can be derailed if the definitions of ‘who is vulnerable’ and ‘what services they should receive’ solely rest on the Federal health authorities.

(d) Addressing systemic inefficiencies marring value for health programmes and investments

Our sincere commendation for the Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) cannot be overstated. Its goal of enhancing service delivery across the sector is welcoming. However, the challenge of aligning funding and local health priorities remains, as reported in a Cross-Programmatic Efficiency Analysis (CPEA).

There are concerns about subnational health authorities lacking evidence of their health priorities and casually producing Annual Operational Plans (AOPs), perhaps due to the lack of real-time evidence transmission from health facilities to health authorities. Also concerning are the weak planning and research departments, poor supervisory practices, and suboptimal attention to Charts of Accounts. Going forward, health partners may consider investing in addressing these fundamental concerns at the subnational. The reason is to ensure that the country’s health system builds a strong culture for quality control and can make sustainable progress even when donors are no more.

In addition, SWAp and other health authorities must look into the insecurity crises affecting the functionality of primary health facilities across the country. Undoubtedly, places affected by terrorism and banditry are high risk, but we see insecurity tensions also in slum areas and non-slum urban settlements. The evidence available to us shows that insecurities faced by PHCs have increasingly taken a national outlook, making a national PHC-security agenda unavoidable. Local and national strategies to address this threat have become imperative.

(e) Build and enhance systems to drive health anticorruption and accountability

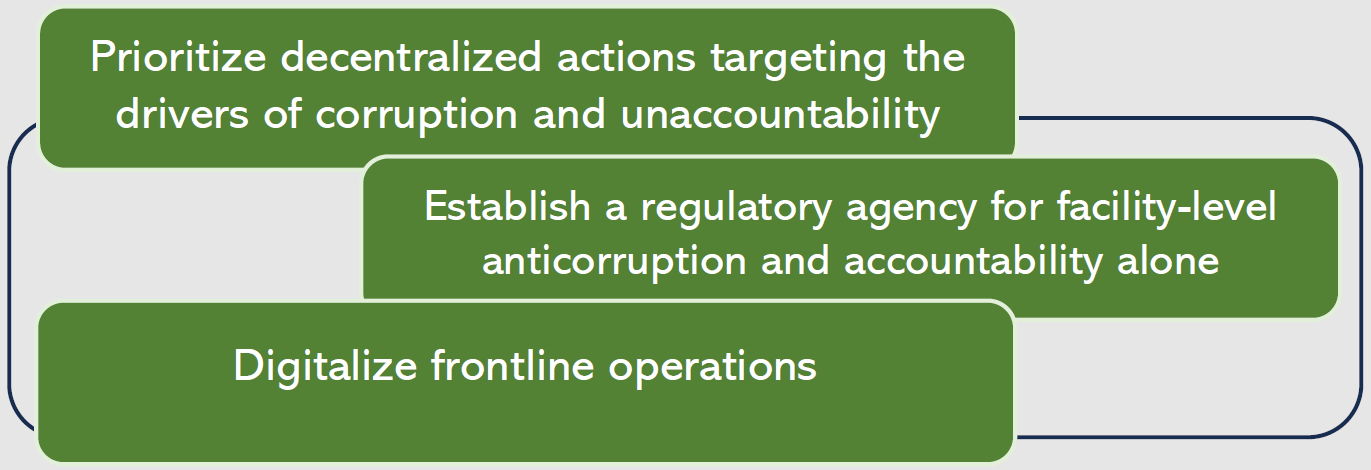

On July 18, 2024, the Minister for Health and Social Welfare was emphatic about the health sector significantly affected by corruption. For more than 7 years, HPRG has studied health corruption in Nigeria, culminating in setting up a coalition. We acknowledge efforts in setting up SWAp, including the anticorruption unit at the FMoHSW to challenge health corruption and improve accountability. However, for these efforts to yield the desired result, they must be facility-centred and driven by the subnational.

Also, we cannot sufficiently address corruption if the systemic drivers continue to thrive, enabled by the actions and inactions of health authorities. Decentralised Facility Financing (DFF) model for PHCs will only work when PHCs and health units in the Local Government Areas (LGAs) are given statutory monthly allocations. There is an ongoing “privatization” of PHCs by facility managers who invest their private resources to keep facilities running, including employing volunteers. Expectedly, they are compelled to pursue their profits, even to the detriment of the service users. So, when the BHCPF is disbursed, there are justifications for kickbacks and mismanagement.

Our lessons from studying health corruption are clear about the intersecting areas in the image below.

The non-justiciability of health rights in Nigeria is a critical issue. Without legal frameworks, it would be difficult for citizens to hold the health systems accountable. It is about time Nigeria should consider empowering citizens with the right to enforce their health rights through the law courts.

Conclusion

As critical friends within Nigeria’s healthcare space, we desire a health system that prioritizes the wellbeing of the Nigerian people and offers commensurate value for every investment. Our 2024 roundup has aligned evidence with policy interests of health authorities, particularly focusing on improving population health. We remain committed to driving meaningful change and, in 2025, we look forward to more progress in the following areas:

- Clear strategy/commitment of RKMD towards aggregating, synthesizing, communicating, and demonstrating the use of evidence from health research in Nigeria.

- Health authorities using evidence-based manuals, protocols, and practices in linking IHPs to the formal health system and aggressively enforcing scope of practices within the informal sector.

- Expansion of health attention and protection to children who are 5 years and above, enforcing the health components of the Child’s Rights Act, and addressing the leadership issues and constraints that have hampered efficient delivery of the National School Health Policy.

- Scale up services in PHCs to holistically address health needs of adolescents/young people, while decentralizing identification of vulnerable groups and the services due to them for effective utilization of the VGF.

- Build partnerships with communities and stakeholders aimed at challenging harmful gender norms and fostering supportive environments where adolescents and young people can access SRHR services.

- Use CPEA’s evidence to reorganise operations of health partners and subnational health authorities to achieve the coordination/accountability objective of SWAp.

- Collaboration between SWAp, the subnational health authorities, and security agencies to establish a physical security agenda/policy for PHCs with clear and realistic operational procedures and targets.

- Facility-centred and Subnational commitments to addressing systemic actions/inactions that sustain corruption and accountability issues in the health sector, especially at service delivery points.

Our team wishes everyone Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.

Professors Obinna Onwujekwe and Benjamin Uzochukwu

On behalf of the Health Policy Research Group, University of Nigeria

Contributors: Prof Chinyere Mbachu, Prof Enyi Etiaba, Dr Prince Agwu, Ifunanya Agu, Chinelo Obi

Click to download PDF version of the 2024 Roundup

Acknowledgement: We thank all our funders, partners, and collaborators for an eventful 2024 and looking ahead to 2025.

How to cite: Health Policy Research Group (2024). HPRG’s health sector 2024 roundup: evidence, knowledge, politics. https://hprgunn.com/hprgs-health-sector-2024-roundup-evidence-knowledge-politics/