By the Health Anti-Corruption Project Advisory Committee (HAPAC)

The Health Anti-Corruption Project Advisory Committee (HAPAC) endorses the ‘Red Letter’ issued by Nigeria’s Honourable Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Prof Mohammed Ali Pate, which highlights corruption and its detrimental effects on the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF). In this blog, HAPAC shares its findings from an investigation into the BHCPF in some states in Nigeria, along with proposed anti-corruption strategies. We start by explaining the BHCPF to the public, helping them understand what it is and how corruption hinders access to healthcare at primary health centres (PHCs).

The facts of BHCPF that citizens must know

Under the National Health Act of 2014, Nigeria’s law mandates that 1% of the country’s annual consolidated revenue be allocated to the BHCPF to support PHCs in providing quality health services. Parliament is currently debating a possible increase to 2%. Besides these government funds, donors such as the World Bank and private corporations can also invest in and contribute to the BHCPF.

Once funds are collected for BHCPF, they are allocated to improve health services through four main channels, called gateways. These are:

(a) through the primary healthcare agency, which ensures health facilities are well-equipped, supported in staffing, and stocked with essential drugs.

(b) through the health insurance agency, to extend healthcare insurance to the poor and vulnerable.

(c) via the disease prevention gateway to support disease outbreak response.

(d) and the emergency gateway, which should support ambulance services and patient referrals from PHCs to general and teaching hospitals.

Since 2018, when the government officially flagged the programme, over 110 billion naira [$US 68.3 million], including 32.9 billion naira [$US 22 million] just recently disbursed, have reportedly been invested in the BHCPF. Therefore, we would expect that health services and outcomes in Nigeria should at least reflect this amount of money spent on primary healthcare. Unfortunately, this has not been the case, despite some progress, such as increased primary healthcare utilisation and a decline in the mortality of children under five years old. This is why concerns are now being raised about corruption and its impact on the BHCPF.

A list of corruption issues in the BHCPF

In most facilities visited by HAPAC, we observe clear gaps between the yearly investment, around 1.2 million naira [$800], and the actual tangible results in equipment, infrastructure, and the availability of consumables such as essential medicines. We have identified eight primary corruption issues impacting the success of the BHCPF, listed here for clarity:

- Facility managers pay money to community monitors to overlook and ignore inappropriate practices.

- Facilities submit similar receipts for the purchase of medicines to the Primary Healthcare Agency and Health Insurance gateways. So, they get twice the amount spent on such purchase.

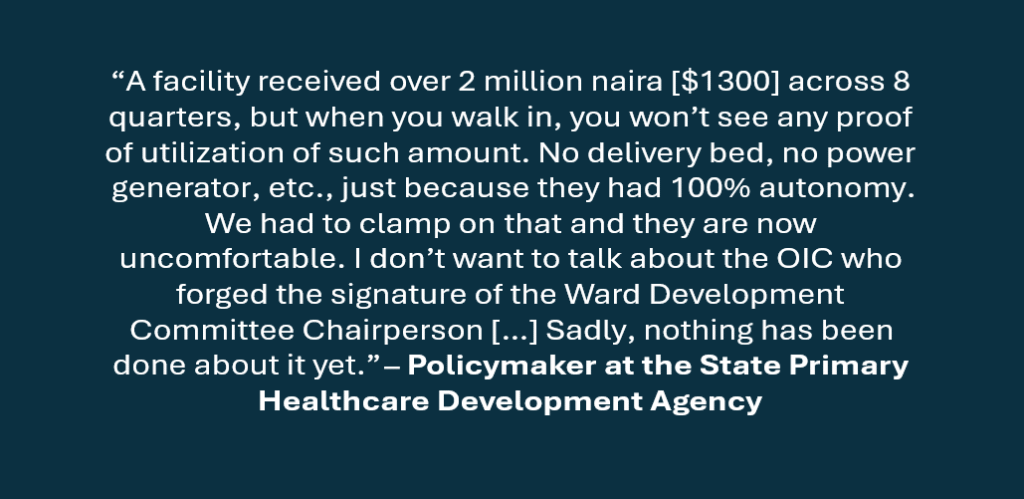

- Falsification of signatures of community co-signatories to obtain funds without the knowledge of the community monitors.

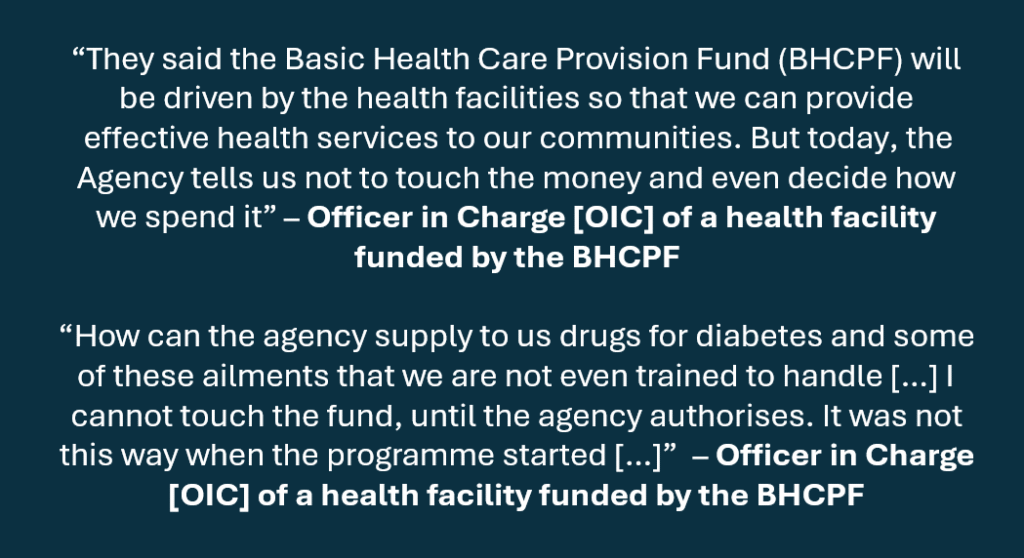

- The State Primary Healthcare Development Agency (SPHCDA) has appropriated to itself the sole authority over funds allocated to health facilities. It directs facility managers on when to authorise transfers, typically made to a bank account they (the SPHCDA) specify.

- SPHCDA assumes responsibility for drug procurement without consulting health facilities and without following the approved bidding processes under Nigeria’s procurement regulations.

- SPHCDA procures and distributes drugs to health facilities at its discretion, rather than following requisition orders that detail facilities’ drug shortages and requirements.

- SPHCDA supplies unsuitable drugs to primary health facilities and disregards feedback from facility managers.

- SPHCDA brazenly supplies health facilities with drugs that are nearing expiration.

The eight issues listed above show that the SPHCDA, health workers who manage facilities, and the supposed community monitors are implicated. We present some salient quotes from our interviewees.

HAPAC’s strategy for anticorruption to ensure the BHCPF yields commensurate value

Our proposed strategies include updating the BHCPF operational guidelines in the future with an anti-corruption focus. The specific anti-corruption measures should encompass: scapegoating; decentralised anti-corruption initiatives; anonymous feedback channels; sanctions and enforcement; training and retraining programmes; and centralised procurement.

Scapegoating: Health workers and their managers frequently behave without fear of consequences, leading to visible acts of corruption. To encourage a culture of compliance with rules, it is essential to implement lawful scapegoating strategies guided by anti-corruption agencies to ensure accountability.

Decentralised anticorruption measures: Partnerships between the health sector and anticorruption agencies exist, but they have not yet influenced frontline operations. It is essential to create and implement a system that connects health facilities directly with anticorruption authorities, such as the anti-corruption unit at the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. While the 774 Performance and Financial Management Officers (PFMOs) offer some assistance and serve as a buffer, they should not replace real-time communication between facilities and anticorruption officials.

Anonymous feedback channels: A key insight from our investigation is that health personnel and managers are willing to report malpractices and corruption that undermine the BHCPF. However, gathering this sensitive information can put their identities at risk. We recommend adding an anonymous feedback mechanism for health staff, managers, and service users in each state’s BHCPF performance review. Moreover, such feedback should be addressed quickly and effectively.

Sanctions & enforcement: Anticorruption agencies should have the authority to investigate and prosecute violations of BHCPF guidelines. Their roles must be clearly defined in BHCPF operational policies, and they should enforce relevant legal actions to ensure accountability.

Training/retraining: Many involved in these corrupt practices either lack awareness of the consequences or are unfamiliar with proper procedures. The BHCPF secretariat should increase the frequency of training and retraining sessions for frontline health workers and their managers on ethics, national and global health priorities, and procurement and BHCPF guidelines.

Central Medical Stores: This should be an opportunity to rethink revitalising the central medical stores (CMS) or drug management agencies at the state level. The CMS is vital for controlling medicine prices in primary healthcare facilities and provides an accountability layer to fight corruption. A single, traceable source for purchases enhances regulation and oversight. Purchasing medicines from the open market risks obtaining substandard or counterfeit drugs and increases the chances of record falsification. Central procurement at the state level, with sufficient plans for sales logistics covering interiors, would naturally help resolve issues related to the falsification of purchase receipts for medicines.

Conclusion

As watchdogs and allies in Nigeria’s health sector, we have noted that ad hoc accountability measures are ineffective and may even enable more corruption. Therefore, anti-corruption strategies must be institutionalised and continuously adapted to counter the evolving tactics of those seeking to exploit the system. Our investigation has identified various corruption scenarios related to the BHCPF, along with potential sustainable solutions based on available evidence. The BHCPF is a significant public health investment for Nigeria. Yet, without robust, systemic accountability, this fund could become another missed opportunity.

About HAPAC: This is a coalition challenging health sector corruption based on evidence, composed of members from academia, civil society, media, anticorruption agencies, and health practitioners.

For correspondence: Contact vbamas@icirnigeria.org and prince.agwu@unn.edu.ng, Cc: obinna.onwujekwe@unn.edu.ng and drndakasha@yahoo.com

This article was first published by the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR)

This work was supported by a research grant from the Health Systems Research Initiative with funding from the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), the Medical Research Council (MRC) and Wellcome, with support from the UK Economic and Social Research Council (grant number MR/T023589/1).